MURPHY DOME AIR FORCE STATION, ALASKA

-An Airman’s Chronicle-

AS TOLD BY DOUGLAS R. HEAD

23 YEARS LATER

The Assignment...

I was home on leave in Independence, Missouri. For some unknown reason, I called back to my duty station, the 24th Norad Region Control Center at Malmstrom Air Force Base, Great Falls, Montana when I received the news, "Head you’re going to Murphy Dome". I’d heard about Murphy Dome three years earlier when assignments were handed out at Keesler A.F.B., Biloxi, Mississippi. I remember feeling remorse for the one or two guys in my class who drew the short straw for a remote assignment on one of Alaska’s Distant Early Warning (DEW) line stations. While I had heard of most of the remote assignments in Alaska’s Far North, Murphy Dome always seemed to be the most prominent name in my subconscious thinking. The Air Force’s Manpower Planning Systems had worked flawlessly in my case. I was to report to Murphy on September 13th, 1976. This date was aligned precisely to coincide with my scheduled discharge date of September 12th, 1977. Since all remote assignments in Alaska were for a twelve-month period, I had been caught.

My flight out of Seattle on Alaskan Airways had provided me a short glimpse into the vast beauty of the Alaskan Wilderness far below. The Chugach Mountains coming into Anchorage and Cook Inlet on final approach awed me. Anchorage’s airport terminal featured an impressive sportsman’s display. Mounted trophy King Salmon and enormous Kodiak Bears lined the airport’s corridors. I had brought plenty of fishing gear along with my Remington 700 .30-06 and Ruger .357 magnum. I had visions of playing out some of my boyhood sporting fantasies that had been spawned by countless hours of reading Outdoor Life magazines and Herters Catalogs. I must confess that I was equally, ok, more awestruck by the beauty of the Japan Airlines Flight Attendants that seemed to be parading by me as if to say, " take a good look, it might be a long time before you see this again". They were right, so I paid very close attention.

After my ten day Arctic indoctrination was completed at Anchorage’s Elmendorf Air Force Base, I boarded a Wien Air Alaska flight bound for Fairbanks. Guys from Murphy met Sid Duffer and I at the Fairbank’s terminal and after loading our gear into the navy blue extended cab 4x4 government truck and a quick stop at the post office, we departed Northwest driving towards my new home, the 744th Aircraft Control and Warning (AC &W) squadron, the " Eye’s of the North". As we continued driving along the narrow gravel access road, I was again impressed with the tall white birch, aspen and pine trees lining our path. Nearing Murphy Dome and half way up our long hill (a 7 mile jaunt), I was experiencing the first snow storm of the season and one that would essentially hide the tundra from me until the following May.

I vividly recall walking into our small Orderly Room to deliver my PCS orders and hearing several of the guys make snide remarks about how long I had to go and how short they were. They even referred to me and each other with numbers that I soon determined meant how many days they had remaining at this very special place. I failed to sense much humor in the small office and in fact felt a strong cloud of despair and seriousness in the faces of my new family. Outside, the late afternoon darkness and blowing snow seemed to be in synch with what I was feeling inside. Little did I know that this unique culture and ambience had been established over many previous years and would remain for the most part, intact for the duration of my tour.

In the middle of my first night, the Air Force Security Police from Eilson Air Force Base decided it would be fun to spring a surprise drug bust on us. They arrived quietly and woke us up without much discussion or fanfare. After a couple of futile hours, they left disappointed with their drug sniffing dogs. I saw no evidence of any drug use in my year at Murphy.

Murphy Dome, part of the Alaskan Air Command and Norad was the Region Control Center for the Northern half of Alaska. The site was completed in 1951 and was designed to accommodate a larger staff than the other DEW line sites. The small facility was a typical military designed single story all wooden structure. Local legend told of a Captain Murphy who when flying an early surveying and construction flight in heavy fog crashed the helicopter he was piloting into the Southeast knoll of the hill and was killed. Thus the appropriate naming of Murphy Dome. When I was stationed there, remains of the fuselage remained at the point of impact some 100 or so yards down from the hill’s Southeast summit. Due to recent budget cuts in the early 70’s, Murphy personnel had been reduced and as a result, we had the luxury of one man per room.

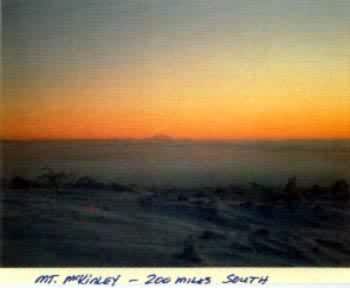

We were located on a rounded hilltop at only 3,000 feet but well above the timberline. On a clear day, the majesty of Mount Mckinley could be observed 200 miles to the South of us. When the atmospheric conditions were just right we were treated to a psychedelic light show compliments of the Aurora Borealis. The beauty of the area was without equal.

We had seven outlying radars that fed data to our first generation air defense computer. Our darkened Operations Center (Ops center) was painted black inside and appeared very much like a very small Movie Theater with three levels of radar consoles and associated equipment. We operated with three crews, Alpha, Bravo and Charlie and worked six days on and three days off. During the six-day work cycle, we would work two swings, two mids, and two day shifts. With the exception of our 30 day January joint military Arctic war game, "Operation Jack Frost", our schedules were pretty routine. During "Jack Frost" we combined into two crews and worked 12 hour shifts for 30 days.

I had a rather desirable position as Identification Coordinator, which basically meant I had the responsibility to evaluate and determine the friend or foe nature of all aircraft in Northern Alaskan airspace. If, I could not make a positive I.D. on a given plot, I would declare the aircraft unknown and we would aggressively begin determining the most appropriate course of tactical action. These monthly events always included calling our F4 fighter alert shacks at Eilson and Galena. Our pilots would routinely plead with us to authorize their launch, and on several occasions, we obliged. At this point, our controllers along with the now outdated SAGE (Semi Automatic Ground Control) systems would jointly direct the geometry of the impending intercept(s).

Our friends the Soviets were masterful at knowing exactly where our Air Defense Identification Zones (ADIZ) were located and routinely flew directly along on top of them. In addition, we had our share of illegal Polar Bear hunters who flew low and slow along the Western coastline in search of trophy game. Tin City, our westernmost radar site, always had initial contact with them and over time, we both grew accustomed to knowing their identity.

While we would often scramble fighter aircraft to go chase a distant intruder, we did have one rather unique set of uninvited guests. Two Russian Badgers crossed into our Western airspace and proceeded full tilt into the Alaskan interior on a heading towards Fairbanks. These boys were coming fast and we kept thinking they’ve got to turn around. We may have called this one to late. When we did finally launch two F4’s out of Eilson, we soon recognized that in order for our pilot’s to make a visual I.D. on the now retreating Soviets they would need to drop their tip tanks loaded with JP4 and punch their afterburners. This plan, while effective in securing the intercept, represented a 50-50 chance on return fuel availability. Our fighter jocks pleaded to press on so rather than hear them bellyache, we agreed to the strategy. After catching the Badgers at the ADIZ to wave hello, our crews made it home safely, on fumes.